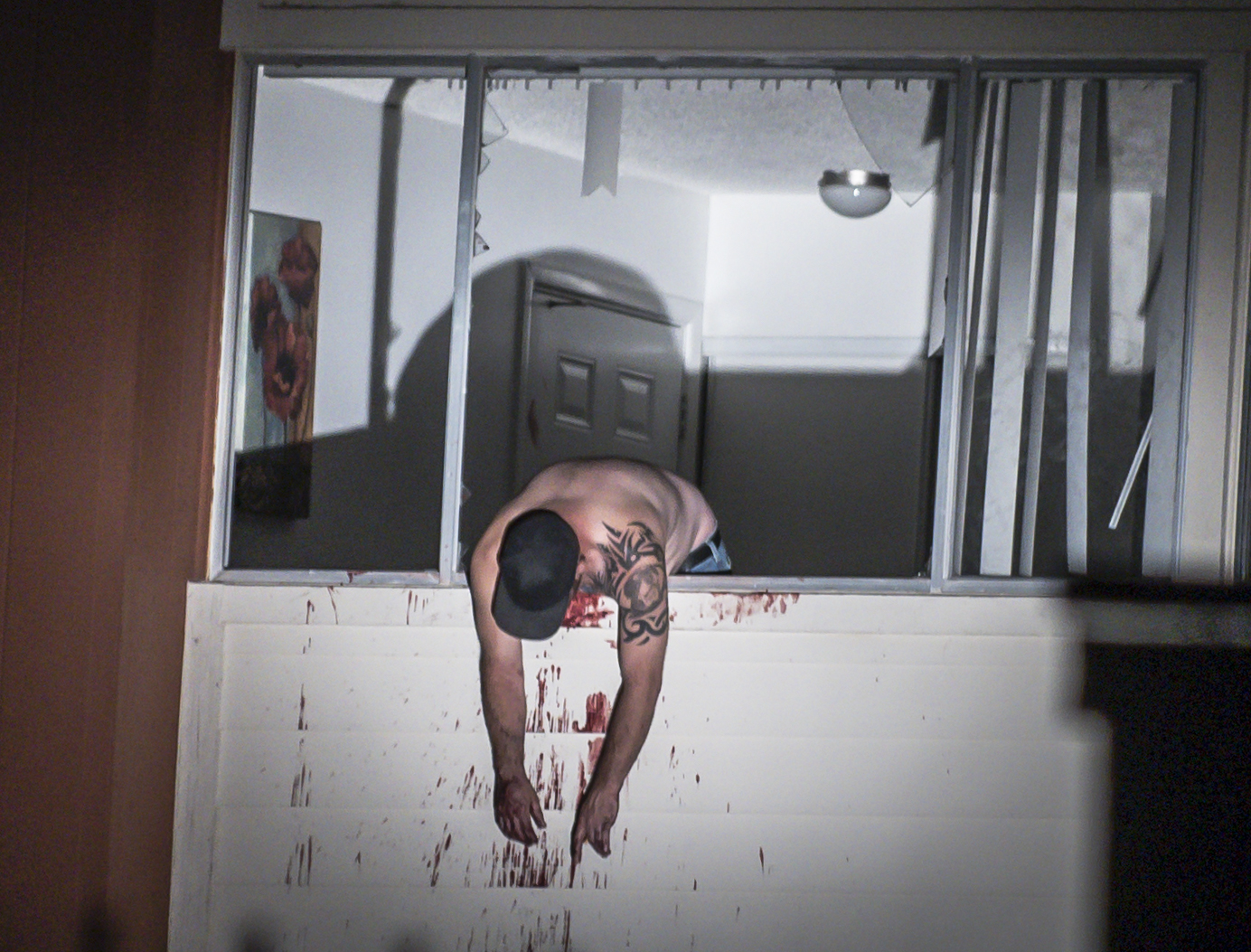

Elementary School put on Lockdown

APD officers respond to a possible active shooter near the Air Force Base forcing a local elementary school to go on lockdown.

(NY TIMES article) Video of Police Shooting Prompts Protests in Albuquerque

The police in Albuquerque used tear gas Sunday night to disperse hundreds of demonstrators who marched downtown to protest police shootings, including the shooting of a mentally ill homeless man whose death was captured on video by a camera attached to a police officer’s helmet.

The protest was prompted by the March 16 shooting of the homeless man, James Boyd, 38, who was camping in the Sandia foothills when he died in a standoff with the police. In a graphic video that was released by the police department and has gone viral, Mr. Boyd appears to be turning away when he is shot. The police said he was brandishing two knives. Six live rounds were fired.

The mayor, Richard Berry, called the shooting of Mr. Boyd “horrific.” He asked the United States Justice Department to investigate, and he dismissed the police chief’s description of the shooting as “justified” under the law.

Since last year, the Justice Department has been investigating the Albuquerque Police Department for possible civil rights violations and excessive use of force. In the last four years, police officers have been involved in nearly two dozen fatal shootings.

Anonymous, the hacking collective, urged people to take to the streets on Sunday to demonstrate over the shooting of Mr. Boyd and against what it described as the police department’s excessive use of force. In addition to hundreds of demonstrators on the street, police officials acknowledged, their website was taken down by a cyberattack for several hours on Sunday.

The protest began peacefully around noon on Sunday, The Albuquerque Journal reported.

Then it went beyond a “normal protest,” Mayor Berry said. He praised the police response. The police, including officers on horseback, used more than two dozen canisters of tear gas on Sunday night. At least five people were arrested.

Roberto E. Rosales, a photojournalist and a former photo editor at The Albuquerque Journal, posted several photos from the protest on Twitter.

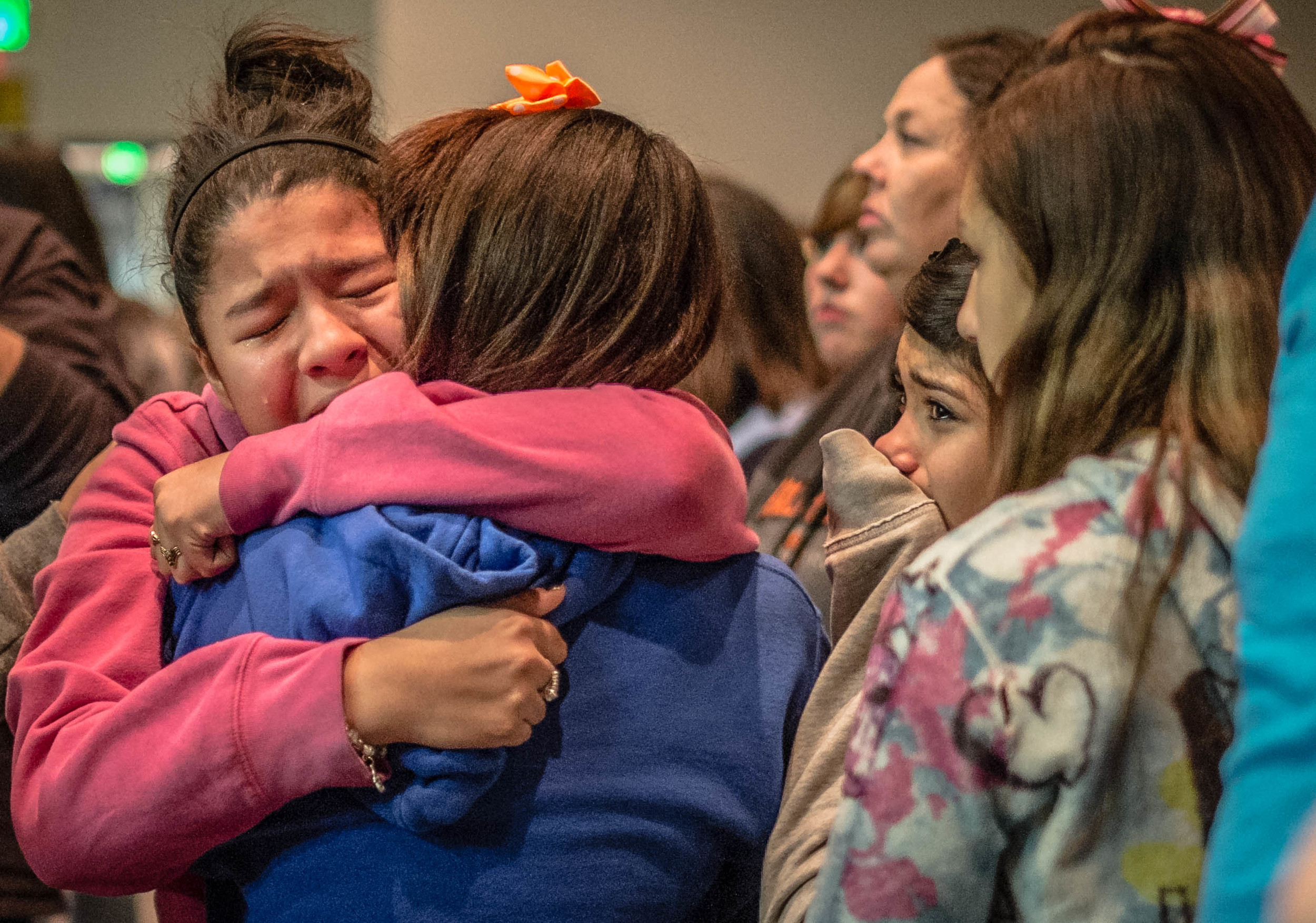

Protest over Albuquerque Police Shooting

This was the scene the morning after James Boyd, a homeless man, was shot by police in the foothills of the Sandia Mountains. This event caused outrage in the community and eventually led to a huge protest this past Sunday, two weeks after the shooting.

Albuquerque Police begin to throw tear gas at protesters on Central Avenue near the University of New Mexico.

Albuquerque riot police force protesters off the streets on Central Avenue.

Whitehorse Lake sees flowing water at last

Chee Smith Jr., chapter president at Whitehorse Lake on the Navajo Nation, tests a new water line extended last month to the home he shares with his father in the remote, water-starved community. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal

By John Fleck/Albuquerque Journal Staff Writer

WHITEHORSE LAKE – Chee Smith Jr. may have hauled his last water.

Outside his trim yellow home near the eastern edge of the Navajo Nation, a line of blue stakes marks the path of a water pipe leading to a spigot that now pokes through the dry dirt behind his house.

Smith flipped the handle to demonstrate the water’s flow, but turned it off quickly. Water here, even when it comes in a pipe rather than being hauled in the bed of a pickup, is not a thing to waste. “Water is gold out here,” Smith explained. “It’s our life.”

A bowl of water and hand soap are fixtures in homes like those of 87-year-old Chee Smith Sr. at Whitehorse Lake, where indoor plumbing is arriving for the first time in the Navajo Nation community. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Inside the house, a sink and toilet await the final hookup that will bring a clean water supply and indoor plumbing to what might be one of the most water-starved regions in the United States.

Every home in this sparse community at the foot of Tse’ Yi’ Gai – White Mesa – has an outhouse, a basketball hoop, and the water tanks, barrels and buckets that accompany a life without running water.

The buckets are for the relatively short drive to the Whitehorse Lake chapter house, where they’re filled with safely drinkable water. For a dollar, community members can take a shower there, too. It’s a longer drive to one of the windmill-fed stock tanks to fill the 50-gallon barrels Smith uses to haul water for his family’s six goats and the two trees outside the house. “We haul it daily,” Smith said.

The network of blue stakes leading outward from the big new water tank at the foot of the mesa is a signal of change. In November 2012, 24 Whitehorse Lake homes were connected to the newly arriving water lines. Last month, the home Smith shares with his 87-year-old father, Chee Smith Sr., was among the next 21 homes to be connected, with the final plumbing now underway to connect the indoor plumbing to the water lines and newly dug septic systems carved into the hard desert earth behind each house.

“Once they hook up, they don’t have to haul any more,” the younger Smith said.

Smith, the 51-year-old president of the Navajo Nation’s Whitehorse Chapter (something like a mayor, Smith explained) left the community as a young man, earning an engineering degree from Brigham Young University and working in Tucson for eight years after college before returning. “I came back to help my community,” he said.

Lack of indoor plumbing and the need to haul water by pickup truck are common on the Navajo Reservation. But even by Navajo standards, Whitehorse Lake and the other communities along the nation’s eastern fringe are dry. The area averages less than 9 inches of precipitation a year. Groundwater, the normal fallback for desert communities, is of poor quality, when it can be found at all, said Andrew Robertson, an engineer with Souder, Miller and Associates in Albuquerque.

But that is slowly changing. Whitehorse Lake – an hour’s drive north of Grants, two hours south of Farmington – is at the southwestern end of a growing spiderweb of water pipes passing through what Robertson called “the most water-starved” communities on the Navajo Nation.

The 13-mile Phase 4 of the Eastern Navajo Water Pipeline Project brings water south from Pueblo Pintado to Whitehorse Lake. For now, the $3 million extension connects to a modest groundwater supply system at Ojo Encino, a Navajo community near Cuba. Eventually, plans call for an expanded network of pipes to connect to the north Cutter Reservoir and a more permanently reliable supply of water from the San Juan River via the $73 million Cutter Lateral project.

The Cutter Lateral, in turn, is part of the Navajo Gallup Water Supply Project, intended to bring water to some 100,000 people across the Navajo Nation in western New Mexico who currently lack access to a clean and reliable water supply.

Whitehorse Lake got its name for white horses that used to run the arid landscape and a pool that used to build after storms behind a hand-built earthen dam. All but the name – and 700 people tied by generations to the land – are gone now. “People like it out here,” Smith said. “They stay out here.”

But water, or its lack, has always been a central feature of life here. Of the area’s 700 residents, 550 had no running water to their homes before the water pipeline project began. Smith remembers hunting firewood in the canyons to the north and having his father teach him where to dig a foot or two into the sandy soil to find pools of shallow groundwater. “It’s real clear,” he said. “You can drink it.”

“That’s how people survive out here,” Smith said. “They know where all the water holes are.”

During the winter, family members would pack big bowls full of snow and bring them home, setting them by the fire to melt. “For generations, the people have melted the snow,” he said. Before pickups were common, water haulers used horse-drawn wagons, something common as recent as Smith’s childhood in the 1960s. “That was almost like a full-day job,” he said.

The public health implications for the communities that lack running water are enormous, Robertson pointed out. A 2007 federal study, noting that a wide variety of diseases are common without access to clean water, put the health care savings of the Navajo Gallup Water Supply Project at $435 million over 20 years. “There is a clear connection between sanitation facilities (water and sewerage) and Indian health,” the study concluded.

With the expansion of the water system, Whitehorse Lake is seeing young families move back to the community who had left to live in surrounding cities, Smith said. And he sees economic opportunities.

As he drove east from the chapter house toward his home, Smith pointed to a broken-down building that until 1985 was home to a community store. Nearby, the community has set aside a parcel to build a new one. Before the water project, replacing the store and other steps forward in Whitehorse Lake’s economic development were hard to carry out. Another possibility is building a restaurant for drivers passing through on N.M. 509, the highway up from Grants. But that would require something most restaurant owners take for granted – a reliable water supply.

“Due to no water,” Smith explained. “That’s why we have no development in the community.”

She’s American, he’s Mexican: They’re caught in limbo

Raymundo and Emily Cruz walk on the esplanade under the X sculpture by the Mexican artist known as Sebastian, which Emily in her blog has called a symbol of Ciudad Juárez’s renewal, “the promise of a new beginning.” (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

CIUDAD JUÃREZ – “I cried myself to sleep that night thinking I had made the biggest mistake in the world. I cried because I felt stupid, homesick, spoiled, lost, sheltered, weak, and most of all scared (expletive) of what was to come.”

Emily Bonderer Cruz left her home in Arizona to start a new life in this border city three years ago with her husband, Raymundo, even as thousands of people were fleeing this same city at the height of a violent drug war.

The Cruzes found themselves trapped in a little-known purgatory of the U.S. immigration system, along with an unknown number of other couples advocates say could number in the thousands or tens of thousands. She is a U.S. citizen; he is Mexican. When the two met in 2005, Raymundo was working without legal documents and had crossed into the United States illegally twice – landing him with a lifetime ban from the country that, despite their later marriage, made him ineligible to apply for a pardon for a decade. The 10-year clock would only start ticking once he left the country.

So, the couple packed their possessions and, in 2010, drove through New Mexico into Texas and over the border to wait it out.

And blog about it.

Sharp-tongued and witty, Emily curses liberally in English and Spanish, and launched a blog that would eventually draw media attention and become a point of reference for other couples living in Ciudad Juárez and other border towns under similar circumstances: The Real Housewife of Ciudad Juárez. She vents, she marvels, she agonizes, but she also makes the best of what many have described as a sad and bitter situation.

“I could be pissed off all the time and angry at my country all the time, and run around Juárez with a frown on my face and be angry at the world,” she said one recent afternoon in an interview at her home. “Ideally, I didn’t want to be here. But life isn’t … . You don’t always get what you want.”

She ended her first blog post in August 2010, about the night she cried herself to sleep, with a repetition like a mantra, as if to convince herself, “This is a romantic adventure. This is a romantic adventure. This is a romantic adventure.”

‘ To go back and start over’

Emily Cruz isn’t a housewife. She and her husband live largely off what she makes working in El Paso in administration, while Raymundo works long hours at a maquiladora assembling auto harnesses for about 600 pesos per week, roughly $46. That is a “big difference,” he said, from the $600 he earned weekly making ice cream at a restaurant in Arizona.

“For us, it is really a moral issue,” said Randall Emery, president of American Families United, which is lobbying Congress to relax the laws that dictate yearslong or lifetime bans for immigration violations. “Here you have people who may have done something in the past, but they have left to do things the right way. People have suffered tremendously and will continue to suffer until there is some kind of resolution.”

New Mexico Republican Rep. Steve Pearce has co-sponsored a bill, H.R. 3431, with Texas Democrat Beto O’Rourke, that would grant authorities greater discretion in reviewing past minor or technical immigration violations, or those that occurred when the spouse was underage.

Pearce, who opposes a Senate bill that takes a broad approach to immigration reform, says he would prefer to see reform happen piecemeal, starting with an issue such as the plight of married couples like Emily and Raymundo Cruz.

“I feel that we ought to be taking this thing in bite-sized chunks instead of in big packages,” he said.

While it is unlikely that immigration legislation, large or small, will get aired in the House of Representatives until later in 2014, Pearce said legislators who have reviewed the bill, “no matter their political affiliation, they think this is a case of doing the right thing.”

The number of undocumented immigrants who are ineligible for residency despite being married to a U.S. citizen is unknown, but it’s possible to get a sense of how many people are affected: Some 9 million people belong to a family that includes at least one adult unauthorized to live in the U.S. and one U.S. citizen child, according to the Pew Research Center.

Shawna Avila considers New Mexico her “home base.” She and her husband are among the unknown number of couples who have chosen to stay in the U.S. in hopes that the law might change. Her husband, Roberto, first crossed illegally from Mexico to the U.S. when he was 17, did so more than once, and is ineligible to apply for residency although they have been married for more than six years. Shawna says that, because her parents live in New Mexico, she shared her story with Pearce.

“Even though he was very conservative, he seemed to have a willingness to listen to individual stories on immigration,” she said.

Emily Cruz drives to pick up her husband, Raymundo, at his job at a maquila where he builds harnesses for a global automotive supplier manufacturer for less than $50 a week. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Her parents live in Quemado, Catron County, where she is now moving with her newborn.

The limitations Roberto faces as an undocumented immigrant have kept them apart for the past two years. It made it difficult for him to follow her to Miami, where she was pursuing a doctoral degree in sociology before their daughter was born. Now, he has a higher paying job in Tennessee that would not be available in New Mexico.

“We’ve gone through many ups and downs through the years,” Shawna said. ” … I’ve supported immigration reform ever since I found out about it.”

‘Feel more free’ in Juárez

On the other side of the border, Raymundo – who describes himself as serious and Emily as the fun one who brings the “party” home – worries about safety. He was picked up by thugs in downtown Juárez when he first arrived, dragged into a basement and beaten, and says he is still scared to go out. He is studying for a high school diploma and wants to go to college. But most of all, he wants to return to the U.S.

“The truth is, I would like to go back and start over and work,” he said. “I love it. I really like the United States. It’s not that I don’t like Mexico, but I feel that there are more opportunities there. I feel safer; I feel better there.”

But they live in Juárez and seem determined to explore the city’s sunny side, despite Raymundo’s well-founded fears and a tight budget.

Emily recently posted a “Weekend in Pictures,” which included a snapshot of a soda machine with a five-step how-to that had her in stitches; stills from a movie she watched; stray dogs in a convenience store parking lot; artistic graffiti on a cement-block wall; a picnic in Chamizal park and a horseback ride; eating food samples at Sam’s Club; and sneaking around the side of a blue-and-white striped circus tent to get a glimpse of the animals (she blogged that they didn’t have the cash to attend).

They might be simple pleasures, but they contrast with the constrained life she felt forced to live in the U.S.

“We couldn’t live our life there,” she said. “We didn’t feel comfortable doing anything. We wouldn’t go to a birthday party, because there might be like a checkpoint … . I feel much more free here.”

Emily Cruz enjoys a break with her husband, Raymundo, at a favorite bar in Ciudad Juárez called Shadow Davidson. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

‘It’s all real’

Emily doesn’t want or expect to be a symbol for immigration reform. She writes openly about a past methamphetamine addiction (she has been sober from drugs for seven years but still drinks “like a fish”); a post called “Sexico” about sex and Mexico is one of her most popular; she never graduated from college; and doesn’t clean up her language much.

But her candid way of writing about her experience, her largely positive attitude about Juárez and her hope that she might have a chance to bring her husband to the U.S. in the future have inspired others. Comments on her blog from other “exiles” in Mexico constantly thank her, sympathize with her, cheer her on.

Veronica Perez moved to Juárez in March 2013, after she married her husband Roberto, who is from Mexico City. He had a couple of illegal crossings in his past; they applied for a pardon and it was initially granted, then taken away. When questioned about crossing illegally, Roberto answered honestly and U.S. authorities gave him a lifetime ban.

Devastated and having spent their $10,000 in savings on the paperwork, the couple decided to “leave a nice, comfortable life” in Austin to wait for reform, or a chance at a waiver after 10 years, in Juárez.

Veronica, a graduate of New Mexico State University, struggled to find a white-collar job in El Paso, so she works in landscaping “wearing a safety vest and a hard hat and some boots” while Roberto earns $100 a week roofing in Juárez.

“We’re both very bitter,” she said in a telephone interview. “We tried to go the legal path. If I had to do it all over again, I wouldn’t.”

She describes how “disheartening” it was when they first arrived in Juárez, how both struggled with their decision and the marriage suffered. Then a friend sent her a link to The Real Housewife of Ciudad Juárez “and the dark clouds went away.”

Emily “brought a lot of peace into our hearts,” she said. “There were other couples there, some she already knew and some who contacted her through her blog.”

Several women met and exchanged stories.

“It’s comical and it’s sad, and, at the end, it’s all real,” she said. “Finding these other ladies, it brought a little hope to us.”

Emily says today that living in Juárez has “completely changed” her by teaching patience – especially in the inevitable long lines at the international bridges – and putting what she has into perspective.

She wrote last month, “I could survive on nothing more than Coke Zero, brandy, sausage, egg and cheese biscuits, chicken wings, calzones and Tin Roof Sundae ice cream. And love. Everybody needs a little love.”

This is Emily's blog: http://therealhousewifeofciudadjuarez.blogspot.com/

BITES FROM THE BLOG

What “The Real Housewife of Ciudad Juárez” has to say in her blog about:

CURSING:

“When I began to live half my life speaking only Spanish, it was only natural that I began to swear in my second language as well … much to my husband’s disgust. He says my choice of words embarrasses him, that I sound like a naca, a cualquiera, a callajera. Ghetto. … You know, when I am speaking to people, sometimes I see a gleam in Ray’s eyes. A little glint of pride behind all of his embarrassment. Maybe it’s because he’s proud of my Spanish even though he doesn’t approve of my choice of words. Maybe it’s because he wishes he could express himself so freely, even to strangers. I’m not sure. All I know is that this is me, and everyone is going to have to just take it or leave it.”

— Sunday, December 14, 2013, “The V Word”

FAMILY:

“We have family traditions. Even though we are just a scrape of a family, here on the border, hundreds of miles from my family in the US, hundreds of miles from my husband’s family in Mexico. We are still a family. Every Tuesday, we have ‘Midweek Movie Night.’ The tradition probably came from the fact that Redbox has new releases every Tuesday. Yes, in a country where pirated movies are sold on every corner and cost less than an item from the 99 Cents Only store, we still splurge for a rental once a week.”

— Saturday, November 2, 2013, “Naufragos Y Inmigrantes”

FOOD:

“Hi, my name is Emily and I am a Nutellaholic. The discovery of the Kinder Bueno solidified my addiction to sugar and hazelnuts in a way I wouldn’t wish upon my worst enemy. Our friends over at Ferrero describe this candy as a hazelnut cream filled wafer with a chocolate covering. I think a more accurate description would be ‘God Himself hugged by a crispy coat of angelic perfection and dipped in orgasms.’

I guess that’s why I’m not in advertising.”

— Sunday, December 15, 2012, “My Top 10 Mexican Junk Foods”

THE BORDER:

“The (Rescue) mission (which serves the homeless) is located smack dab on the US/Mexico border, just steps away from The Border Highway. You could spit and it would land in Juarez. I became overwhelmed with the idea of what it would be like to grow up on the other side of that line in the sand, where the only things that separate you from opportunity are some green and white SUVs, a piece of paper and a whole lot of politics. … I imagined what it would be like to dream of having an education and all the opportunities that the US provides, and it all being so close you can almost taste it. I imagined what it would be like to be a little kid, living in a cardboard house, looking to the US with a fire in my eyes … pining after a better life.”

— Wednesday, December 21, 2011, “Rescue Mission”

Wells Blog

Duis mollis, est non commodo luctus, nisi erat porttitor ligula, eget lacinia odio sem nec elit. Maecenas faucibus mollis interdum. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue.